I don’t think I can go back…

I was out walking in the woods near my home when a message came in from my best friend:

“We are locked down for at least another three weeks”

It was what I needed to pop the bubble of grief that had been stuck halfway up my chest all day, and I sat down on a low branch and had a cry.

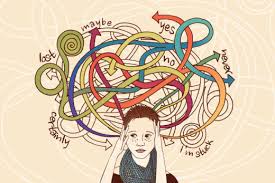

I’ve been feeling frustrated with the expression “when things get back to normal”. Firstly because there is no “back”. There is always only ever “next”; only “forward”. Maybe the right word semantically is “resume”. But more than semantics and chronology, it will surely be impossible to pick up where we left off because individually, collectively, economically, socially -we are all being changed by This. The effects of this virus have been far beyond biological; it has reached into the existence of every single organism on our planet. Into eco-systems, stock exchanges, air quality, family dynamics, neighbourhood networks, supply chains, and Prime Minsters’ experiences of love…

The effects of this virus have reached into and mutated my will for the future. Because even if it were A Thing, I don’t think I could go back. And yet I feel very scared that nevertheless, I will. That I will choose to. That I will be expected to. Needed to.

I’ve been attempting to figure out whether my reaction to Lockdown is best characterised in terms of the relieved emergence of my ‘secret introversion’, or whether it perhaps reveals that I was personally burning out. But exploring this with my closest friends, and reading some of the truly brilliant articles cropping up online like here, here and here, it seems that I am far, far from alone.

I cried just now out of pure relief that I have at least another three weeks of living this much smaller, quieter life, where I exercise on my gym mat daily, pray daily, cook daily, and weave a dance from 8am to 8pm between online sessions with clients and hanging the laundry out, preparing for the next session and taking care of personal admin, listening to a CPD recording and walking up the hill and through the woods behind the house. Where I sleep till 7 not 5. Where I wake naturally not yanked by the hair by my alarm clock. Where I have enough energy, it seems (and I didn’t know it was because I was too tired; I thought I just secretly didn’t really want to do it), to go dancing (in my front Zoom), to chat across the fence to my neighbours, to join in online social events, and yes, like everyone else, to bake (hence the daily exercise on my mat…).

I also feel scared, and really angry.

I don’t know who precisely to be angry with. Economists? The leaders of the Industrial Revolution? Myself? The Man? The best analogy I can think of is the frog in the saucepan thing. It’s like I was one of – we were – the frogs in Frog Boiling Experimental Group B, happily swimming around in water that was actually getting hotter and hotter.

Acclimitising, rationalising, dissociating, denying, entirely unaware that I was being boiled alive, when someone accidentally knocked the saucepan off the stove. Now I’m on the kitchen floor, shocked, experiencing the relief of the absence of something I didn’t even know I didn’t want. But up above my head, I can see someone preparing a fresh saucepan of water, and I don’t know where the door is.

As always, with all my “lockdown” posts – I know I’m not speaking for frontline workers, the sick, the people who’ve lost loved ones, or their income. But I do think I might be speaking for an incomprehensibly large number of people across the globe who have been accidentally handed the balance in their life, and the reordering of their priorities, that they’ve been bone-deep longing for as long as they can remember.

And I don’t know what to do, but I don’t see how I can willingly climb back into the saucepan. Since I was in my late teens and early twenties, nothing has affected me enough to elicit a resistance-level-conviction in me that I would lay down in the road, chain myself to a railing, or go on strike to honour.

But if there’s a Don’t Go Back movement, I’ll be there at the railings on the day the lockdown is lifted. I am worse than ignorant when it comes to economics, but I refuse to believe there isn’t an economic recovery model that insists on preserving balance, dethroning the tyrant of unfettered profit and unmoderated growth, and refusing to rely on exploitation.

And that’s exploitation writ large and writ subtle, in the form of middle class overworking and modern-sense resistant stigmatising of the basic need for time to do anything other than work sleep and repeat with a good measure of feeling you’ve failed because you still didn’t call your Dad, do any exercise, or eat anything that wasn’t straight out of a packet.

As any recovering addict knows, pain is the touch-stone of growth, and desperation is a gift. We have been forced into a change that no business or political party and very few individuals would choose unless their back was against the wall. But now that we’ve seen, will we allow ourselves to forget what we discovered? Will we allow ourselves to forget what it was like to have time for living? It’s not the moon on a stick. I’m not campaigning for the right to crotchet tofu three times a day or advocating that we all sit in the lotus position until our joints dissolve into enlightened stardust, and neither am I championing sitting on ever expanding home-baked backsides watching Neflix either.

I just think it’s ok for us to insist on having time, and clean enough air, to breathe.